Patients with osteoarthritis (OA) often present with one or more chronic comorbid conditions. A vicious cycle of OA, pain, disability, obesity, and comorbidities can significantly impact OA disease progression and management as well as the treatment of other conditions.

DOWNLOAD PDFIncreased Comorbidity and Mortality

Twenty-five percent of Americans have two or more chronic conditions, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and osteoarthritis (OA). In older adults, OA is the most common condition to co-occur with other chronic conditions. A number of comorbidities and co-existing conditions often occur in patients with OA.1

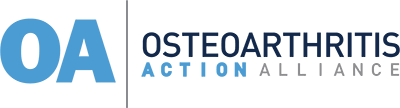

Osteoarthritis and Comorbidities1,35,36,49,50

This infographic can be downloaded as a PDF or PNG.

While OA is not often considered a fatal disease, studies have shown that people with OA, particularly those who are obese, are at higher risk of mortality. There are several possible explanations for OA’s increased risk of mortality, not the least of which is that OA is inextricably tied to other chronic conditions.

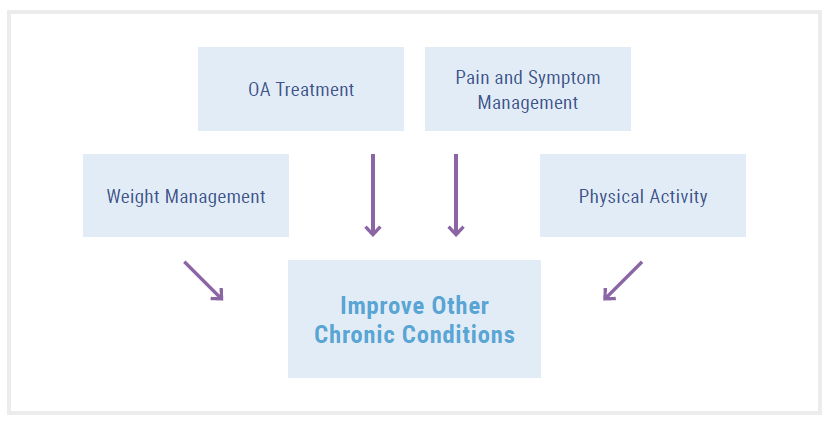

Prompt and adequate management of OA can not only improve patients’ joint symptoms but may have mediating effects on patients’ other comorbid conditions as well.2,3

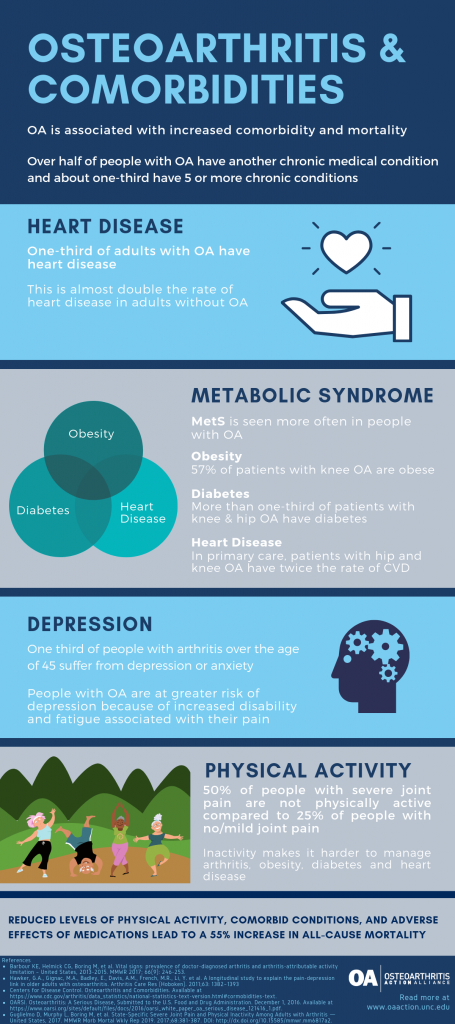

Relationship between OA & Comorbidities

While advancing age, physical inactivity, and obesity likely explain the high prevalence of OA with other chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, the relationship between OA and other comorbidities is complex.

ADVANCING AGE

OA is not a normal part of the aging process, yet age is one of the greatest risk factors for developing OA. The prevalence of comorbidities increases with age; 80% of people over 65 have more than one chronic condition, so it stands to reason that OA, as one of the more common chronic conditions, would be more common in aging adults.4 Aging-related changes in joints at the matrix and cellular levels create conditions conducive to the development of OA.5 Chronic, low-grade inflammatory processes called “inflammaging” occur in all aging tissues and may contribute to the development of OA and help explain the connection of OA to other chronic diseases such as heart disease.6

REDUCED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Physical inactivity is a known risk factor for most chronic conditions, including heart disease and diabetes, as well as obesity, which, in itself, is a risk factor for many chronic conditions.7 Unfortunately, most adults with arthritis do not meet the recommended physical activity guidelines2,9 Based on the 2015 US National Health Interview Survey, the CDC found that 36.2% of adults with arthritis met the recommended weekly aerobic guideline of more than 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity and only 17.9% met the recommended 2 days of muscle strengthening exercises per week. Only 13.7% of adults with arthritis achieved both the recommended aerobic and strengthening guidelines. Compared to people without arthritis, in age-standardized terms, these rates were 10 percentage points, 6 percentage points, and 7 percentage points lower, respectively. This study also found 75% of adults with arthritis had one other chronic condition, and the likelihood of meeting the recommended physical activity guidelines decreased as the number of comorbidities increased.9

Being physically inactive places people with OA at greater risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity.2

Figure 1- Vicious Cycle: OA, Pain, Disability, Obesity, and Comorbidities

OBESITY

Additional Resource for HCPs: OA Prevention- Connecting OA and Weight

Obesity is a strong risk factor for comorbidities like CVD, hypertension and diabetes. Obesity is also regarded as the strongest modifiable risk factor for the development of OA of the knee. Moreover, it has been associated with higher rates of disability,10,11 which impacts ability to participate in exercise, the first-line intervention for OA and other chronic conditions like hypertension and diabetes. The connection between obesity and OA is both biomechanical and metabolic.

Biomechanical impact of obesity on OA

Excess body weight puts extra stress on weight-bearing joints. Men and women who are obese have a 2.8-fold and 4.4-fold increase in developing knee OA, respectively. For each kilogram (2.2 pounds) of excess weight, the risk of developing OA increases by approximately 10%.10 Someone with ten pounds of additional weight increases the force exerted on their knee by up to 60 pounds with each step.12 Obesity can also change gait mechanics and affects the distribution of weight across bilateral joints, resulting in damage to the articular cartilage and other tissues.13,14

Metabolic impact of obesity on OA

OA and Diabetes15-19

- Diabetes affects approximately 11% of American adults

- People with OA have a 32% increased risk of developing diabetes over a 12-year period

- OA and diabetes have shared risk factors: older age and obesity

- Walking difficulty is an independent risk factor for developing diabetes

- OA may impair the ability to exercise and lose weight

Excess body weight is also associated with an increased risk of OA of the hand, suggesting that metabolic changes related to obesity (not just excessive weight-bearing activities) contribute to the development of OA.20 Metabolic syndrome (characterized by factors including insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and visceral obesity) is more prevalent in those with OA than without.21 In fact, the metabolic pathological changes that occur in a joint with OA have been directly linked to insulin resistance, low bone density, alterations in collagen production and the impact of LDL oxidation on bone formation and development of low-grade synovial inflammation.22

Long-standing, type 2 diabetes is a predictor of severe OA (knee and hip, predominantly) independent of age and body mass index; moreover, patients with type 2 diabetes have a 2-fold increase in the rate of joint arthroplasty.23 OA and metabolic syndrome (MetS) have been linked recently, with consideration given to metabolic OA as a subtype (Met-OA).24-26 While MetS is prevalent in 10–30% of the general population, it is prevalent in 59% of OA patients, often accompanied by severe symptoms and earlier onset.25

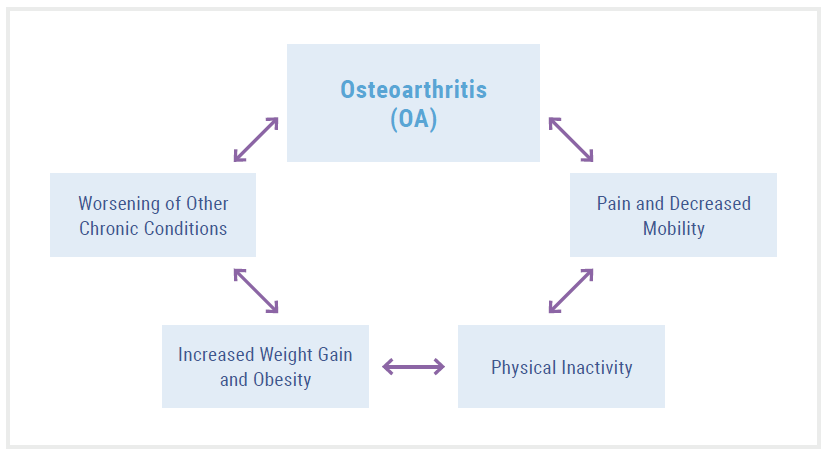

HYPERTENSION AND CVD

Research has demonstrated a relationship between radiographic and symptomatic knee OA and development of hypertension.27 People with knee OA have a higher chance of developing hypertension than those without OA. CVD is also a significant comorbidity among patients with OA; the relationship is complex and includes biological and behavioral factors.28,29 An increased risk of incident heart failure and ischemic heart disease has been observed among people with OA compared with controls.28 OA and CVD share numerous risk factors and markers indicative of causal pathways that cannot be overlooked, including but not limited to chronic low grade inflammation, metabolic syndrome, increased BMI, hypertension, reduced physical activity, and age.2,26,29,30

Use of NSAIDs for treating OA

Oral and topical NSAIDs are the most widely prescribed pain medications for patients with OA.33 However, NSAIDs carry a black box warning because they pose cardiovascular risks (hypertension, heart failure, stroke, myocardial infarction) and should be prescribed with caution. Senior patients are most vulnerable to adverse effects of NSAIDs. In the largest study to date, patients taking NSAIDs were shown to have higher risk of cardiovascular events and some NSAIDs were shown to increase the risk of death fourfold.34 Therefore, people with arthritis who are treated with NSAIDs are at higher risk of cardiovascular events.

Figure 2- OA and CVD31,32

DEPRESSION

One-third of people with arthritis over the age of 45 are diagnosed with depression or anxiety,35 which is three times higher than the general population.1 People with OA are likely at greater risk for depression because of increased disability and fatigue associated with their pain.36 Researchers have also identified a slow gait speed – below a proxy threshold for reasonable independent navigation within a community – as a risk factor for increasing depressive symptoms.37 Concomitant OA and depression often lead to increases in activity limitations, healthcare use, and medical costs.38 People with doctor-diagnosed arthritis report more days in the last month of poor mental health (5.4 days vs 2.8 days for people without arthritis).39

OA Detection and Management Considerations

In patients with multiple comorbidities, the competing demands of managing diabetes, hypertension and cardiac disease often take priority and OA can be overlooked. Given the frequency of OA’s co-existence with these other comorbid conditions, it is important for providers to ask about OA symptoms even if the patient does not present with OA.

Detection of OA, particularly early detection, can better equip providers and patients in selecting the most appropriate management pathway for both the OA symptoms and other comorbid conditions.2,3,8

Figure 3- Early Detection of OA is Key

Physical activity & weight loss as first-line interventions

Pain, stiffness, and disability associated with OA can contribute to lower levels of physical activity, which is critical to controlling chronic conditions like heart disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and even depression. Particularly in the presence of multiple comorbidities and the associated contraindications of certain medications, physical activity and self-management interventions are all the more important in addressing OA symptom relief. While patients may know that losing weight and increasing physical activity can help control diabetes, hypertension, and MetS, they may be less aware that physical activity and weight loss are also the most effective means for managing the symptoms and preventing or delaying the progression of OA.40 The IDEA trial, among others, demonstrated that a 10% weight loss, achieved through a combination of intensive diet and consistent exercise, resulted in a 50% reduction in pain.41 Referring patients to evidence-based physical activity interventions—like Walk With Ease42 and Active Living Every Day43—can help patients reduce pain and manage multiple comorbid chronic conditions.

Addressing pain as a barrier to physical activity

A patient’s ability or desire to participate in exercise therapy (e.g., cardiac rehabilitation, regular physical activity) as a treatment option for heart disease, diabetes, or obesity may be limited as a result of OA-related pain and functional limitations.

It is important for providers to assess patients presenting with other chronic conditions for the presence of joint pain to identify and address this barrier. Providers can reassure patients that exercising with OA is safe and provide resources to patients about specialized interventions, such as aquatic therapy44 or other physical activity programs designed for people with arthritis. Providers can also recommend appropriate pain control measures like acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with specific instructions about dosing around exercise sessions.

Pharmacologic Interventions

Comorbid conditions can complicate medication selection to reduce OA-related pain, especially with regard to analgesia, given the vulnerability of the aging population to adverse drug reactions and medication side effects. For example, NSAIDs may be contraindicated in a patient with uncontrolled hypertension, heart failure, and/or compromised renal function. See the following Table for additional comorbid-related precautions and contraindications.

Table 1- OA Drug Therapy Precautions and Contraindications

| ADVERSE EFFECTS | PRECAUTIONS | CONTRAINDICATIONS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen (APAP) | • Skin rash • Elevated LFTs | • Potential for overdose • Severe hepatic impairment • Chronic alcohol use or cirrhosis | • Doses > 4 grams/day • Hypersensitivity |

| Oral & Topical NSAIDs40,45 FDA warnings are the same for NSAIDs regardless of route of administration; however, topical application appears to be safer with less systemic absorption | • GI ulceration • Bleeding • Acute renal failure • Hyper- tension • Heart failure • Stroke • Myocardial infarction • Elevated LFTs • Skin reactions • Sedation* • Altered mental status* • Falls* *especially in senior adults | • Asthma • Anemia • Advancing age • Renal disease • Hypertension • Diabetes • Heart failure • Chronic alcohol use or cirrhosis • Coagulopathy • History of GI bleed or peptic ulcer disease • High-dose or multiple NSAID use • Concomitant corticosteroid therapy | • Severe kidney disease • Extra-cellular volume depletion • Active GI bleeding or ulceration • CABG surgery • Hypersensitivity DRUG INTERACTIONS: aspirin, warfarin, low-molecular weight heparin, anticoagulants, glucocorticoids, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, ARBs, direct renin inhibitor (aliskiren) |

| Duloxetine46-48 | • Nausea • Consti- pation • Fatigue • Diarrhea • Somno- lence • Skin reactions • Orthostatic hypotension • Sexual dysfunction • SIADH • Urinary hesitancy • Serotonin syndrome • Hyper- glycemia • Falls* *especially in senior adults | • Suicidal thinking/behavior • Bleeding risk • Alcohol use • Liver disease or hepatic impairment • Elevated LFTs | • MAO-inhibitors • CrCl < 30 mL/min • ESRD • Severe hepatic impairment • Hypersensitivity DRUG INTERACTIONS: NSAIDs, antiplatelets, ciprofloxacin, SSRIs, bupropion, tramadol, codeine, tamoxifen, SNRIs, TCAs, linezolid, SSRIs, metaxalone, MAOIs, cyclobenzaprine, St John’s Wort, triptans, methadone |

| Intraarticular corticosteroids | • Injection site reactions • Septic arthritis | • Hyperglycemia • Bone loss | • Hypersensitivity • Immune thrombocytopenia |

| Tramadol46-48 | • Sedation • Respiratory depression • Hypotension • Constipation • Seizures • Serotonin syndrome • Skin reactions • Nausea / Vomiting • Falls* • Altered mental status* *especially in senior adults | • Advancing age • CNS depression • Delirium • Head trauma • Hepatic impairment • Obesity • Prostatic hyperplasia • Psychosis • Renal impairment • Respiratory disease • Sleep-disordered breathing • History of substance abuse | • Severe hepatic impairment • CrCl < 30 ml/min* • Hypersensitivity *Extended release only DRUG INTERACTIONS: SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, MAOIs, alcohol, bupropion, CNS depressants, linezolid, metaxalone, triptans, cyclobenzaprine, St John’s Wort, methadone |

| Opioid narcotics46-48 More potent opioids (e.g., oxycodone) or long-acting opioids should generally be avoided if possible, given their poor benefit to risk ratio for chronic OA pain. | • Sedation • Respiratory depression • Hypotension • Constipation • Skin reactions • Nausea / Vomiting • Withdrawal • Falls* • Altered mental status* *especially in senior adults | • Advancing age • Cachexia • CNS depression • Delirium • Head trauma • Hepatic impairment • Obesity • Prostatic hyperplasia • Psychosis • Renal impairment • Respiratory disease • Sleep-disordered breathing • History of substance abuse | • Hypersensitivity • Respiratory depression • Hypercarbia • Acute or severe bronchial asthma • GI obstruction DRUG INTERACTIONS: CNS depressants, hypnotics, alcohol |

CLINICAL TAKE-HOME POINTS

CLINICAL TAKE-HOME POINTS

-

-

- Osteoarthritis is frequently seen in conjunction with other chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

- The complex inter-relationships between common chronic conditions can complicate OA management and must be considered for each patient.

-

REFERENCES

-

- Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Osteoarthritis: A Serious Disease, submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2016. https://www.oarsi.org/sites/default/files/docs/2016/oarsi_white_paper_oa_serious_disease_121416_1.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2019.

- Cleveland RJ, Alvarez C, Schwartz TA, et al. The impact of painful knee osteoarthritis on mortality: a community-based cohort study with over 24 years of follow-up. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;27(4):593-602.

- Parkinson L, Waters DL, Franck L. Systematic review of the impact of osteoarthritis on health outcomes for comorbid disease in older people. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(11):1751-1770.

- Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple Chronic Conditions Chartbook. In: Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/decision/mcc/mccchartbook.pdf.

- Loeser R. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate; 2018: www.uptodate.com. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 1:S4-9.

- Watson KB, Carlson SA, Gunn JP, et al. Physical Inactivity Among Adults Aged 50 Years and Older – United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(36):954-958.

- Williams A, Kamper SJ, Wiggers JH, et al. Musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):167.

- Murphy LB, Hootman JM, Boring MA, et al. Leisure Time Physical Activity Among U.S. Adults With Arthritis, 2008-2015. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3):345-354.

- Garstang SV, Stitik TP. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(11 Suppl):S2-11; quiz S12-14.

- Jordan JM, Luta G, Renner JB, et al. Self-reported functional status in osteoarthritis of the knee in a rural southern community: the role of sociodemographic factors, obesity, and knee pain. Arthritis Care Res. 1996;9(4):273-278.

- Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center. Role of body weight in osteoarthritis. Available at https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/patient-corner/disease-management/role-of-body-weight-in-osteoarthritis/. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- Guilak F. Biomechanical factors in osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(6):815-823.

- Runhaar J, Koes BW, Clockaerts S, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. A systematic review on changed biomechanics of lower extremities in obese individuals: a possible role in development of osteoarthritis. Obes Rev. 2011;12(12):1071-1082.

- Lipscombe LL, Hux JE. Trends in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada 1995-2005: a population-based study. Lancet. 2007;369(9563):750-756.

- Tuominen U, Blom M, Hirvonen J, et al. The effect of co-morbidities on health-related quality of life in patients placed on the waiting list for total joint replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:16.

- Rahman MM, Cibere J, Anis AH, Goldsmith CH, Kopec JA. Risk of Type 2 Diabetes among Osteoarthritis Patients in a Prospective Longitudinal Study. Int J Rheumatol. 2014;2014:620920.

- Piva SR, Susko AM, Khoja SS, Josbeno DA, Fitzgerald GK, Toledo FG. Links between osteoarthritis and diabetes: implications for management from a physical activity perspective. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(1):67-87, viii.

- Hawker GA, Croxford R, Bierman AS, et al. Osteoarthritis-related difficulty walking and risk for diabetes complications. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(1):67-75.

- Baudart P, Louati K, Marcelli C, Berenbaum F, Sellam J. Association between osteoarthritis and dyslipidaemia: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open. 2017;3(2):e000442.

- Puenpatom RA, Victor TW. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals with osteoarthritis: an analysis of NHANES III data. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(6):9-20.

- Courties A, Sellam J. Osteoarthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus: What are the links? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;122:198-206.

- Schett G, Kleyer A, Perricone C, et al. Diabetes is an independent predictor for severe osteoarthritis: results from a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):403-409.

- Zhuo Q, Yang W, Chen J, Wang Y. Metabolic syndrome meets osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(12):729-737.

- Le Clanche S, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Sari-Ali E, Rannou F, Borderie D. Inter-relations between osteoarthritis and metabolic syndrome: A common link? Biochimie. 2016;121:238-252.

- Courties A, Berenbaum F, Sellam J. The Phenotypic Approach to Osteoarthritis: A Look at Metabolic Syndrome-Associated Osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2018.

- Zhang YM, Wang J, Liu XG. Association between hypertension and risk of knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(32):e7584.

- Hall AJ, Stubbs B, Mamas MA, Myint PK, Smith TO. Association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(9):938-946.

- Rahman MM, Kopec JA, Cibere J, Goldsmith CH, Anis AH. The relationship between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease in a population health survey: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(5).

- Courties A, Sellam J, Berenbaum F. Metabolic syndrome-associated osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29(2):214-222.

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-322.

- Calvet J, Orellana C, Larrosa M, et al. High prevalence of cardiovascular co-morbidities in patients with symptomatic knee or hand osteoarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45(1):41-44.

- Crofford LJ. Use of NSAIDs in treating patients with arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15 Suppl 3:S2.

- Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086.

- Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, Brady TJ. Vital Signs: Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis and Arthritis-Attributable Activity Limitation – United States, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(9):246-253.

- Hawker GA, Gignac MA, Badley E, et al. A longitudinal study to explain the pain-depression link in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(10):1382-1390.

- Hochman JR, Gagliese L, Davis AM, Hawker GA. Neuropathic pain symptoms in a community knee OA cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(6):647-654.

- Lin EH. Depression and osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 2008;121(11 Suppl 2):S16-19.

- United States Bone and Joint Initiative. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS). In: In. Fourth ed. Rosemont, IL. 2018: Available at https://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition. Accessed June 12, 2019.

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(4):465-474.

- Raveendran R, Nelson AE. Lower Extremity Osteoarthritis: Management and Challenges. N C Med J. 2017;78(5):332-336.

- Arthritis Foundation. Walk With Ease. Available at https://www.arthritis.org/living-with-arthritis/tools-resources/walk-with-ease/. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Human Kinetics. Active Living Every Day. Available at http://www.activeliving.info/about-aled.cfm. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- Rahmann AE. Exercise for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis: a comparison of land-based and aquatic interventions. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:123-135.

- Buys LM, Wiedenfeld SA. Osteoarthritis. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, M P, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 10e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Brown JP, Boulay LJ. Clinical experience with duloxetine in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain. A focus on osteoarthritis of the knee. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5(6):291-304.

- Wang ZY, Shi SY, Li SJ, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Duloxetine on Osteoarthritis Knee Pain: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Med. 2015;16(7):1373-1385.

- Cymbalta (duloxetine) [package insert]. In. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control. Osteoarthritis and Comorbidities. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/national-statistics-text-version.html#cormobidities-text.

- Guglielmo D, Murphy L, Boring M, et al. State-Specific Severe Joint Pain and Physical Inactivity Among Adults with Arthritis — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019. 2017;68:381-387. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6817a2.