The most effective means for managing the symptoms and preventing or delaying the progression of osteoarthritis (OA) is through the use of nonpharmacologic therapies.1,2 All management guidelines strongly support the use of nonpharmacologic modalities as initial therapy, but also as concurrent management for OA throughout its progression.1,4-6

Types of nonpharmacologic interventions include:

- Patient Education

- Physical Activity

- Weight Loss

- Assistive Devices, Braces, Taping

- Psychosocial Treatment

- Complementary & Integrative Health Treatments

- Referral to Other Specialties

Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP)

CDSMP teaches useful tools to help manage symptoms related to many chronic conditions. This CDC-recommended program includes sessions on behavior change, goal setting, problem solving, and peer support. CDSMP has been shown to improve: ability to do social and household activities, mental health, reduction in symptoms like pain and increased confidence in ability to manage chronic conditions. A Spanish version of the program, Tomando Control de su Salud, is available.8 Local programs can be found through the Evidence-Based Leadership Council.

PATIENT EDUCATION

Optimal management of OA requires an investment in patient education as all of the initial treatment recommendations require patient commitment. Dispelling misconceptions, (e.g., “I’m just getting old,” “nothing helps,” “progression is inevitable,” “I’m wheelchair bound”), especially about disease progression, the use of narcotics and that exercise will make pain worse, are vital to the success of symptom management and improving the patient’s quality of life (QOL).

Patients should be empowered to manage the day-to-day impact the disease has on their lives. Research has shown that patients with arthritis are interested in learning about self- management strategies, particularly nonpharmacologic strategies for managing their condition.7 By connecting patients to evidenced-based self-management education (SME) programs and services in the community, clinicians can help ensure that they will have the confidence to be an active participant in the management of their OA, helping to prevent short- and long- term health consequences, and achieve the best possible QOL.7

Many patient resources about OA, its symptoms, causal factors, and treatment options are available in this Toolkit.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

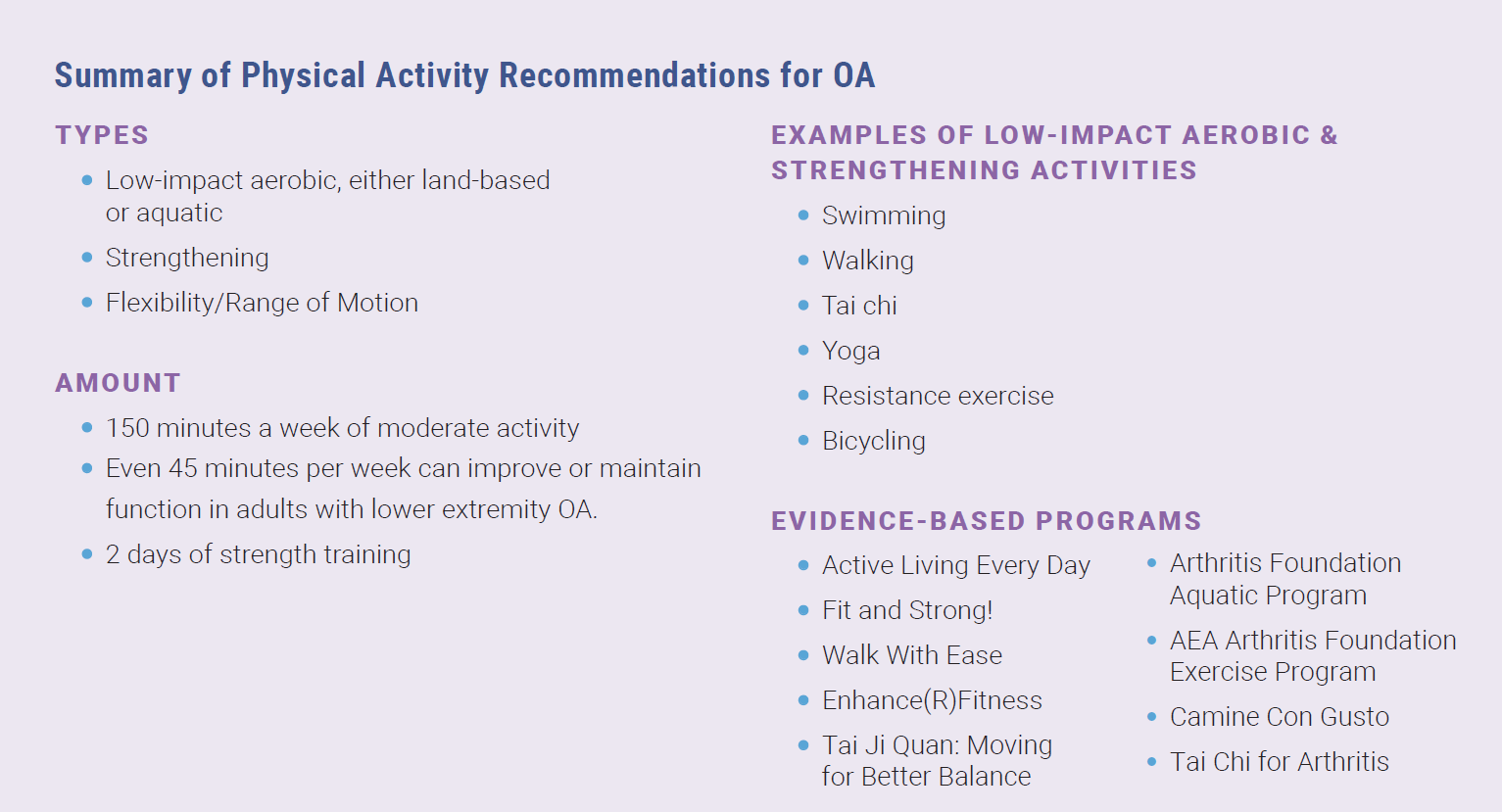

Physical activity and weight management are essential therapies for the management of OA.1 Physical activity improves pain, stiffness, and physical function in patients with OA.3 In a meta-analysis by Wallis et al, patients with severe knee OA who were waiting for a joint arthroplasty had less pain after participating in pre-operative exercise.9 National guidelines recommend 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity physical activity, plus 2 strength training sessions/ week. Moderate intensity activity can be defined as intense enough that an individual can talk, but cannot “sing.” Examples include: brisk walking, slow biking, general gardening, and ballroom dancing.10 These overall guidelines for physical activity among adults can serve as a basis for clinicians’ recommendations. However, Dunlop et al found that as little as 45 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week can improve or maintain function in adults with lower extremity OA.11 Community-based and other physical activity programs can also provide more specific guidance and support regarding physical activity for patients with OA. Utilizing Physical Activity as a Vital Sign regularly can help providers assess if and how often a patient is active and engage with the patient around setting physical activity goals.

Physical Activity As A Vital Sign

Assessing patients’ current level of physical activity is vital when treating patients with OA, just as measuring blood pressure at each clinic visit is vital to the treatment of hypertension. There is not currently a universal approach to this idea of “Physical Activity as a Vital Sign;” however, by using one of several Physical Activity as a Vital Sign measures, like the SNAP, PAVS, EVS, providers can quickly assess patients’ current level of physical activity, and in some cases, even assess patients’ readiness and motivation to become more physically active.3 Read more in the Engaging Patients in OA Management Strategies module.

While physical activity is one of the best treatments for OA, it should be individualized. Consult the Exercise Rx for Arthritis guide and companion patient worksheet to help your patients create a joint-friendly exercise program. If someone hesitates at the notion of “exercise,” then a suggestion to “just move more” may seem more easily accomplished. Simple suggestions for increasing movement during the day include:

- Walk around the house when talking on the phone

- March in place during commercials

- Choose a parking spot away from the storefront door

- Even yardwork and household chores count!

The clinician should also address patients’ fears that exercise or movement will further worsen pain or increase joint damage and emphasize that it can actually help reduce pain and protect the joint. In fact, limiting the amount of “inactivity” may also help with pain reduction.12

Types of Exercise to Consider

Review the Adults and Employees resources to help your patients increase their activity and find community programs that offer these types of exercises. Patients can also use the Exercise Plan Based on Activity Level Guide to create an exercise plan based on their current activity level.

LOW-IMPACT LAND-BASED AEROBIC EXERCISE

Low-impact physical activity is sometimes referred to as “joint-friendly” physical activity because it minimizes the load and impact on weight-bearing joints, especially those that are commonly affected by OA, such as the knees, hips, and spine.2 Walking and biking are some of the most common joint-friendly activities that also have the added benefits of contributing to cardiovascular health and improved emotional health.

LOW-IMPACT AQUATIC AEROBIC EXERCISE

Water aerobics or pool therapy are examples of aquatic exercise, which can improve muscle strength while minimizing joint loading.13 Both land-based and aquatic exercise programs have been shown to be equally effective in improving patients’ arthritis symptoms and overall quality of life. However, in a meta-analysis, Dong, et al., found that participants in aquatic exercise programs had increased adherence rates and satisfaction levels compared to those in land-based programs.14

STRENGTHENING EXERCISES

Strengthening exercises are recommended for patients with knee and hip OA.2 Quadriceps weakness, in particular, can be a risk factor for knee OA.12,15 Loss of leg strength has been connected to increased pain and disability in patients with knee OA. Resistance exercises (i.e., those that use weights or other devices such as bands to provide resistance) can improve pain and function in patients with knee and hip OA.6,15 To get the most benefit, it is recommended that patients participate in resistance exercises two days per week. In addition to leg strengthening, participating in whole body resistance exercises can improve self-efficacy, self-esteem and reduce anxiety and depression.15

FLEXIBILITY AND RANGE OF MOTION EXERCISES

Flexibility and range of motion exercises contribute to cartilage health, protect joints, and improve comfort during routine daily activities. Patients should engage in low-impact, slow and controlled movements that do not result in increased pain.6 Hand exercises, such as range of motion and stretching, may help improve hand pain related to OA.16 Harvard Health Publishing and Creaky Joints share examples of hand exercises for patients on their respective websites.

TAI CHI & YOGA

See more about these practices in the Complementary & Integrative Health section below

Enjoy the benefits of increased physical activity with the S.M.A.R.T. tips below.

• Start low, go slow.

• Modify activity when arthritis symptoms increase, try to stay active.

• Activities should be “joint friendly.”

• Recognize safe places and ways to be active.

• Talk to a health professional or certified exercise specialist.

Sharing the CDC’s S.M.A.R.T. tips with patients can help them feel empowered to start moving no matter what their fitness level or comfort level.17 Patients may find this “Getting Started with Physical Activity for Arthritis” worksheet helpful if they are not accustomed to exercising.

Lifestyle Management Programs for Arthritis

There are a number of evidence-based physical activity programs (AAEBIs) that teach participants to safely increase their physical activity as a way of managing arthritis or other chronic conditions through the integration of aerobic, strengthening, and flexibility exercises.18 A few of these programs are described below; information on all of the recognized AAEBIs can be found on the OAAA website. To help your patients select a program, you can consult this decision aid, “Evidence-Based Community Programs PA Programs at a Glance,” developed by the CDC and American Physical Therapy Association.19

ACTIVE LIVING EVERY DAY

This is a classroom-based program for people who want to become and stay more physically active; participants meet for 1 hour a week for 12-20 weeks. Benefits of this program include: increased physical activity and aerobic fitness, decreased stiffness, and improved blood pressure, blood lipid levels, and body fat.20

FIT AND STRONG!

This group-based fitness program was created for sedentary older adults who are experiencing lower-extremity joint pain and stiffness but is appropriate for all. Classes are 90 minutes, 3 times a week for 8 weeks. One hour of the class is focused on exercise such as flexibility, strength training and aerobic walking. The remainder of the time is spent on health education for arthritis management. This program improves lower extremity stiffness, pain and strength, aerobic capacity and symptom management.21

WALK WITH EASE (WWE)

WALK WITH EASE (WWE)

Arthritis Foundation’s WWE is a 6-week program that offers practical advice on how to walk safely and comfortably, while also providing numerous strategies to help maintain their progress and overcome challenges. In both the instructor-led and self-directed version of WWE, participants are guided through a workbook that educates them on safe walking, exercise safety and symptom management.22

ENHANCE FITNESS

This group-based, informal program was originally designed for older adults, but is open to adults of all fitness levels, is typically held at gyms or other fitness facilities, and can be joined at any time. Classes are usually held for 1 hour 3 times a week. Benefits include increased strength, improved flexibility and balance, increased activity levels, and improved mood.23

Patients should be encouraged to investigate their insurance coverage of evidence-based programs and other physical activity programming through their physical therapy benefits and/or through added fitness benefits such as Silver Sneakers, an exercise program for adults 65 years and older that is covered by many insurance plans. Also, many local gyms or activity centers offer programs tailored for those with arthritis, including land-and water-based exercise activities. Patients can learn more about these programs in the Evidence-based programs for people with OA video and the Dealing with Osteoarthritis or Joint Pain handout found in this toolkit. See Engaging Patients in OA Management Strategies module for specific strategies and frameworks to discuss increasing physical activity levels with patients.

WEIGHT LOSS

In the presence of excess weight, the biomechanical load on weight-bearing joints is significantly increased, disrupting joint integrity and increasing pain. A 10-pound weight loss in someone overweight can reduce the risk of knee OA by 50% and the amount of knee joint loading by 40 pounds.24,25 In the IDEA trial (Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis), participants with knee OA who were overweight and who achieved a modest weight loss (10% of body weight) through diet and exercise, achieved a 50% reduction in pain scores.26 Weight loss counseling is a key component to successful weight loss in patients. The CDC reports that adults with arthritis who are overweight or obese and who receive provider counseling about weight loss are four times more likely to attempt to lose weight; yet, fewer than half of those adults are actually receiving such counseling.27 Primary care providers can engage patients in weight loss counseling with successful strategies such as motivational interviewing to better advise and assist the patient, guiding the patient to programmatic resources, and educating patients that even small amounts of weight loss can significantly reduce joint load and pain and is also achievable.28

More tips and resources for patients can be found on the Obesity Action Coalition website. The OAC is a patient advocacy organization that offers a wide variety of brochures, guides and fact sheets on obesity and related topics including osteoarthritis.29

See Engaging Patients in OA Management Strategies module for specific strategies and frameworks to discuss weight management with patients. A patient handout about Prevention and Self-Management strategies, including weight management is also available in this Toolkit.

PRACTICAL TIPS FOR MANAGING WEIGHT

- Practice mindful eating- think about the taste and feel of the food and how you are feeling while eating; avoid watching television or reading while eating so you can be aware of how your food tastes and your body feels

- Eat a healthy snack like a salad or piece of fruit before a meal (or party) to avoid overeating

- Pre-portion snacks rather than eating straight from the package

- When eating out, ask for a to-go container at the start of the meal and wrap up half the portion before eating

- Drink water instead of sugary beverages. Add fruit slices or drink sparkling water to make it more appealing

- Stay full longer by replacing high calorie foods with things that have higher water and fiber content like beans, whole grains, broths, fruits and vegetables

- Consult a dietitian for more tips and counseling

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight & Obesity: Fact Sheets and Brochures. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/resources/factsheets.html

ASSISTIVE DEVICES & OTHER EXTERNAL TREATMENTS

In combination with the lifestyle factors mentioned above, assistive devices can provide another layer of non-pharmacologic treatment for patients.1,2 Canes, braces, taping, and some orthoses (particularly for the hand) may provide some benefits for patients, but such interventions are best guided through referral to an occupational or physical therapist specializing in their use1.

Braces

In some instances, using a brace helps reduce pain and improve stability for those with OA. For example, knee braces, which come in a variety of types and materials, can help take pressure off the part of the joint that is most affected by OA.1 Whether choosing a universal size brace or a custom-fit brace, the added stability of the device can provide a sense of confidence to the wearer, helping them feel less compromised and unsteady or like a joint might buckle under weight.32 Getting input from a physical therapist is useful for selection and fitting of an appropriate brace.

Kinesiotaping

While kinesiotaping has shown promise in reducing pain among those with hand (first carpometacarpal)1 and knee OA,1,33,34 it should be introduced by a physical therapist trained in the practice, and patients should be educated about proper techniques and skin care.35

Thermal Modalities

The application of thermal modalities (e.g., ice or heat) to the affected joint(s) may also be employed. Although the effectiveness of this modality is not consistently demonstrated in clinical research, it has been shown to provide temporary relief in some patients, and is very safe.1,2

PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTIONS

As a chronic condition with no cure and significant symptomology, OA is a disease that can have a cumulative effect, both physically and emotionally. People with OA, compared to those without, are at greater risk for developing anxiety and depression36,37 which can impact patients’ participation in several types of activities: routine activities of daily living, life-giving activities like hobbies and spending meaningful time with family and friends, and self-management activities like exercise.36 Pre-existing depression and anxiety, may also impact a patient’s ability or desire to participate in self-management activities.37 A multi-faceted and individualized treatment plan for OA is needed to address social support, sleep, coping skills, and mental health.36 Combined with pain control (e.g. medication, acupuncture, water therapy, etc.) many of the self-management programs mentioned earlier in this module — particularly CDSMP — expose patients to pain coping strategies, social support and self-care practices, which may also contribute to improved pain and physical function. A referral to mental health professional may be warranted in some cases.

COMPLEMENTARY & INTEGRATIVE HEALTH TREATMENTS

More than 30% of American adults use treatments that are not typically considered mainstream. These may include natural products and mind and body practices, many of which were developed outside traditional Western practice.38 Nonpharmacologic complementary and integrative health treatments for OA include mind and body practices such as acupuncture, deep breathing, yoga, tai chi, meditation, massage, and relaxation techniques among others. Some encouraging research has been published on acupuncture, tai chi and yoga.1

Acupuncture

Acupuncture uses the insertion of slender metal needles into the skin at targeted points in the body which is thought to trigger the release of enkephalins, endorphins, and possibly cortisol which may be the mechanism by which some patients experience a reduction in OA pain. While the effectiveness of acupuncture varies, it has provided pain relief to some patients1,39 and is a reasonable recommendation for interested patients. Acupuncture may be beneficial for patients with hand, knee, or hip OA.1

Tai Chi

Tai chi is a form of exercise from China that utilizes slow movements to enhance muscle strength, improve flexibility and balance. Tai chi is recommended for patients with hip and knee OA.1 Tai chi has been shown to reduce the risk for falls in older adults.41 The Arthritis Foundation’s Tai Chi Program has demonstrated improvements in pain, fatigue, stiffness, and helplessness that were sustained one-year following program participation.42 Tai chi can be performed individually or in a group setting.

Yoga

Yoga is a form of exercise that combines focused breathing and mindfulness with physical activity. For patients with arthritis, particularly of the knee,1 yoga can help patients increase their flexibility and strength 43,44 as well as develop breathing and relaxation techniques to help combat painful arthritic flare-ups.43

REFERRAL TO OTHER SPECIALTIES

As with most chronic conditions, the management pathway for each patient will vary, but an interprofessional approach — where patients work closely with a team of health care providers (podiatry, PT/OT, orthopedics, sports medicine, mental health, rheumatology, dietician/nutritionist, naturopaths/ integrative medicine) — is crucial for determining an actionable plan for ongoing disease management. Ascertaining Information, such as the number and specific joint(s) involved, degree of functional discomfort and level of impairment, weight or body mass index (BMI), and overall health status, including other chronic conditions, will facilitate a patient-specific management plan and help determine which additional specialties might be beneficial. Common referrals are to Physical Therapy (PT), Occupational Therapy (OT), and Orthopedics, although many others play an important role in caring for patients with OA (see table below).

Referral to PT or OT should be considered when functional deficits are noted.45 These disciplines can provide manual and/ or exercise therapy to help improve activity, balance, and gait. These specialists should also be consulted when employing the safe and effective use of an assistive walking device (e.g., cane, walker) or in selecting and fitting an appropriate brace. Older adults or those whose balance is compromised due to arthritis may benefit from community-based falls prevention programs to improve agility and strength as a means of reducing injury risk.46

For patients with more severe knee or hip OA, a referral to Orthopedics for consideration of surgery (e.g., joint replacement, arthroplasty) or intraarticular injections may be necessary when non-operative interventions have failed. Up to 20% of patients who undergo total joint replacement surgery report significant long-term pain despite having surgery.47 Patients identified at higher risk of lasting and diffuse pain despite having had surgery are those who have widespread pain, significant pain preoperatively, high body mass index, co-morbidities and depressive symptoms.48

The following table describes the unique attributes and contributions of the various specialties involved in the care of patients with OA. Many of these descriptions were provided by experts in the respective professions.

Table 1: Common specialties involved in the care of patients with OA

SPECIALTY |

CONTRIBUTION TO OA PATIENT CARE |

| Primary care provider (MD, NP, PA, etc) |

|

| Podiatrist |

|

| Physical Therapist |

|

| Occupational Therapist |

|

| Registered Dietitian Nutritionist |

|

| Mental Health Provider |

|

| Athletic Trainer |

|

| Certified Exercise Professional/Personal Trainer |

|

| Sports Medicine Physician |

|

| Rheumatologist |

|

| Orthopedist |

|

| Naturopath/Integrative Medicine |

|

Additional Resources

Meneses SR, Goode AP, Nelson AE, Lin J, Jordan JM, Allen KD, et al. Clinical algorithms to aid osteoarthritis guideline dissemination. Osteoarthr Cartil 2016 Sep;24(9):1487-99.

Raveendran R, Nelson E. Lower extremity osteoarthritis: Management and challenges. NC Med J 2017; 78(5):332-336.

Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: the Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;43(6):701-12.

Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1745-1759.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:220-233.

The Movement is Life™ Shared Decision support tool is intended to be used with patients with chronic knee pain. This framework was designed to support a discussion between healthcare providers and patients to help patients see the impact of their treatment choices over time. Patients will receive a projection about their pain and function level if they “do nothing” compared to if they engage in specific treatments (a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options) such as weight loss, increased physical activity, Physical Therapy and pain medications. Watch this 30-minute Lunch & Learn recording about the Shared Decision Making tool, featuring Charla Johnson, DNP, RN, ONC.

The 2019 American College of Rheumatology and Arthritis Foundation updated guidelines for the management of knee, hip, and hand OA are now available. Watch this 30-minute Lunch & Learn recording about the updated guidelines, featuring Amanda Nelson, MD, MSCR, RhMSUS.

Engaging Patients in OA Management Strategies Presentation & Speaker Guide– Highlights self-management strategies for OA and provides example frameworks to help providers support their patients’ lifestyle changes.

CLINICAL TAKE-HOME POINTS

CLINICAL TAKE-HOME POINTS

-

-

- Physical activity and weight management are the most effective approaches to OA management.

- An interdisciplinary approach to OA care is essential and should be individually tailored to meet the patient’s goals.

-

REFERENCES

-

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:220-233.

- Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The chronic osteoarthritis management initiative of the U.S. bone and joint initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43(6):701-712.

- Golightly YM, Allen KD, Ambrose KR, et al. Physical Activity as a Vital Sign: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E123.

- Meneses SR, Goode AP, Nelson AE, et al. Clinical algorithms to aid osteoarthritis guideline dissemination. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(9):1487-1499.

- Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1125-1135.

- Cibulka MT, White DM, Woehrle J, et al. Hip pain and mobility deficits–hip osteoarthritis: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(4):A1-25.

- Murphy LB, Brady TJ, Boring MA, et al. Self-Management Education Participation Among US Adults With Arthritis: Who’s Attending? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(9):1322-1330.

- Self-Management Resource Center. Chronic Disease Self-Management (CDSMP). Available at https://www.selfmanagementresource.com/programs/small-group/chronic-disease-self-management/. Accessed February 26, 2019.

- Wallis JA, Taylor NF. Pre-operative interventions (non-surgical and non-pharmacological) for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis awaiting joint replacement surgery–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(12):1381-1395.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. In: Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018: Available at https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/pdf/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2019.

- Dunlop DD, Song J, Lee J, et al. Physical Activity Minimum Threshold Predicting Improved Function in Adults With Lower-Extremity Symptoms. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(4):475-483.

- Hunter DJ, Eckstein F. Exercise and osteoarthritis. J Anat. 2009;214(2):197-207.

- Rahmann AE. Exercise for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis: a comparison of land-based and aquatic interventions. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:123-135.

- Dong R, Wu Y, Xu S, et al. Is aquatic exercise more effective than land-based exercise for knee osteoarthritis? Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(52):e13823.

- Vincent KR, Vincent HK. Resistance exercise for knee osteoarthritis. PM R. 2012;4(5 Suppl):S45-52.

- Donvito T. 8 Daily Arthritis Hand Exercises that Can Soothe Your Pain Creaky Joint’s Living with Arthritis Blog Web site. Available at https://creakyjoints.org/living-with-arthritis/hand-exercises-for-arthritis/. Published 2018. Accessed Accessed 2.23.19.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity for Arthritis. Available at www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/physical-activity-overview.html. Published 2018. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Osteoarthritis Action Alliance. Arthritis-Appropriate, Evidence-based Interventions- AAEBI. Available at https://oaaction.unc.edu/aaebi/. Published 2021. Accessed August 4, 2022.

- American Physical Therapy Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evidence-Based Community Programs: Physical Activity Programs at a Glance. Available at https://www.apta.org/contentassets/8af7aa55337d4a94aad3aa1f64006f5f/arthritis-programs-decision-aid.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2019.

- Human Kinetics. Active Living Every Day. Available at http://www.activeliving.info/about-aled.cfm. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- Fit & Strong! Available at https://www.fitandstrong.org/. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- Arthritis Foundation. Walk With Ease. Available at https://www.arthritis.org/living-with-arthritis/tools-resources/walk-with-ease/. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Enhance Fitness. What is EnhanceFitness? Available at http://www.projectenhance.org/EnhanceFitness.aspx. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Garstang SV, Stitik TP. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(11 Suppl):S2-11; quiz S12-14.

- Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, DeVita P. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2026-2032.

- Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1263-1273.

- Guglielmo D, Hootman JM, Murphy LB, et al. Health Care Provider Counseling for Weight Loss Among Adults with Arthritis and Overweight or Obesity – United States, 2002-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(17):485-490.

- Rose SA, Poynter PS, Anderson JW, Noar SM, Conigliaro J. Physician weight loss advice and patient weight loss behavior change: a literature review and meta-analysis of survey data. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(1):118-128.

- The Obesity Action Coalition. Public Educational Resources. Available at https://www.obesityaction.org/get-educated/public-resources/. Accessed August 9, 2019.

- Mushtaq S, Choudhary R, Scanzello CR. Non-surgical treatment of osteoarthritis-related pain in the elderly. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2011;4(3):113-122.

- Riskowski J, Dufour AB, Hannan MT. Arthritis, foot pain and shoe wear: current musculoskeletal research on feet. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(2):148-155.

- Mayo Clinic. Knee Braces for Osteoarthritis. In:2017: Available at https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/knee-braces/about/pac-20384791 Accessed February 23, 2019.

- Lee K, Yi CW, Lee S. The effects of kinesiology taping therapy on degenerative knee arthritis patients’ pain, function, and joint range of motion. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(1):63-66.

- Hinman RS, Crossley KM, McConnell J, Bennell KL. Efficacy of knee tape in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee: blinded randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;327(7407):135.

- Handbook of Non Drug Intervention Project T. Taping for knee osteoarthritis. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(10):725-726.

- Hawker GA, Gignac MA, Badley E, et al. A longitudinal study to explain the pain-depression link in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(10):1382-1390.

- Sharma A, Kudesia P, Shi Q, Gandhi R. Anxiety and depression in patients with osteoarthritis: impact and management challenges. Open Access Rheumatol. 2016;8:103-113.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name? 2018. Available at https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- Acupuncture: NIH Consensus Statement. 1997;15:1-34.

- Lee MS, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Tai chi for osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(2):211-218.

- Huang ZG, Feng YH, Li YH, Lv CS. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Tai Chi for preventing falls in older adults. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e013661.

- Callahan LF, Cleveland RJ, Altpeter M, Hackney B. Evaluation of Tai Chi Program Effectiveness for People with Arthritis in the Community: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Aging Phys Act. 2016;24(1):101-110.

- Bar J. How yoga can help you comabt the effects of osteoarthritis. Cleveland Clinic. HealthEssentials Web site. Available at https://health.clevelandclinic.org/how-yoga-can-help-you-combat-the-effects-of-osteoarthritis/. Published 2017. Accessed April 26, 2019.

- Haaz S, Bartlett SJ. Yoga for arthritis: a scoping review. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37(1):33-46.

- Raveendran R, Nelson AE. Lower Extremity Osteoarthritis: Management and Challenges. N C Med J. 2017;78(5):332-336.

- National Council on Aging. Falls Prevention: keeping older adults safe and active. Available at https://www.ncoa.org/healthy-aging/falls-prevention/. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000435.

- Hawker GA, Badley EM, Borkhoff CM, et al. Which patients are most likely to benefit from total joint arthroplasty? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(5):1243-1252.

- American Podiatric Medical Association. Patients & The Public: What is Arthritis? 2019. Available at https://www.apma.org/Patients/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=977. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Brakke R, Singh J, Sullivan W. Physical therapy in persons with osteoarthritis. PM R. 2012;4(5 Suppl):S53-58.

- Walker-Bone K, Javaid K, Arden N, Cooper C. Regular review: medical management of osteoarthritis. BMJ. 2000;321(7266):936-940.

- Stamm TA, Machold KP, Smolen JS, et al. Joint protection and home hand exercises improve hand function in patients with hand osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(1):44-49.

- American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. What is a sports medicine physician? SportsMedTodaycom. 2019. Available at https://www.sportsmedtoday.com/what-is-a-sports-medicine-physician.htm. Accessed May 23, 2019.