Injury prevention programs and weight management strategies may prevent symptomatic OA from occurring and have the potential to preserve wellness and quality of life for individuals and reduce the national burden of OA.

DOWNLOAD PDFAdditional Resource for HCPs: OA Prevention- Connecting OA and Weight

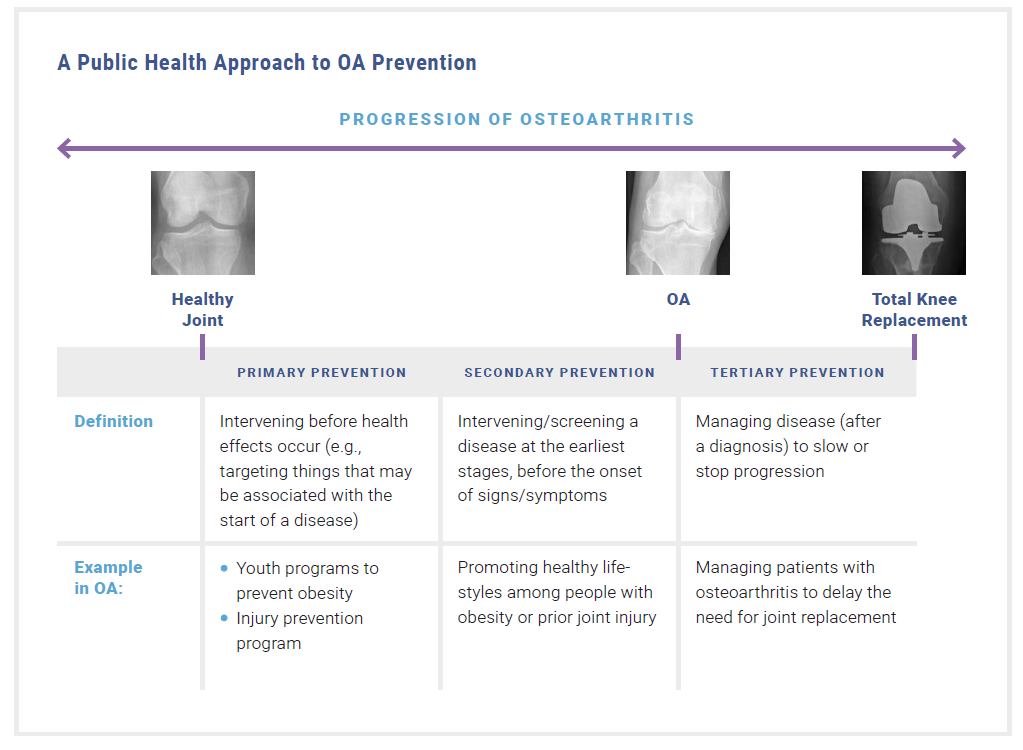

The field of public health focuses on disease prevention through three levels of activities: primary prevention (intervening before health effects occur), secondary prevention (intervening in early stages of a disease, before the onset of symptoms), and tertiary prevention (managing the disease to slow the progression, which is covered in the Clinical Management of OA module).1 Injury prevention and weight management strategies span these three levels of activities in the context of preventing osteoarthritis (OA). This module takes a public health approach to primary and secondary prevention of OA through focusing on weight management and injury prevention strategies.

Injury prevention and weight management strategies may prevent symptomatic OA from occurring and have the potential to preserve wellness and quality of life for individuals and reduce the national burden of OA.2

Figure 1: A public health approach to OA prevention

Primary Prevention

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

Clinicians should encourage individuals with a normal body weight to maintain or adopt a healthy lifestyle that involves physical activity and healthy diet to help preserve a normal body weight. Higher body mass index (BMI) is not only a major risk factor for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer and premature death but is also implicated as a cause of OA.3 Excess weight increases the biomechanical load on weight-bearing joints, which can disrupt joint integrity and lead to pain.

**New Resource** Find out what the adult obesity prevalence is in your state with the CDC’s Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps.

Clinicians should focus on obesity prevention among all age groups, including children, by promoting healthy individual level behaviors. These behaviors may include reducing sugary drink consumption, reducing screen time and other inactive behaviors, increasing physical activity, and choosing food options low in solid fats, calories, and added sugars.4 Clinicians can also work with communities to promote the availability of healthy options for eating, physical activity in school, and accessible areas to be physically active in a community.5

Weight Management Resources

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed resources to promote individual-level and community-level efforts to prevent and manage obesity.

Resources for individuals: Printable handouts for patients include tips on fruits and vegetables, portion size, healthy beverages, and more.

Community efforts: Community efforts should focus on policies and programs to support healthy eating and active living in a variety of settings such as early childhood care, hospitals, schools, and food service.

The Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) is a patient advocacy organization that offers a wide variety of brochures, guides and fact sheets on obesity and related topics including osteoarthritis.

INJURY PREVENTION

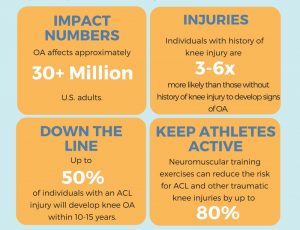

Injuries resulting from occupational activities, sports, or accidental falls, are known to be risk factors for subsequent OA development. Previous traumatic joint injury (e.g., a fracture) places someone at higher risk of developing OA in the affected joint(s). Post-traumatic OA makes up approximately 12% of all OA cases and can result from injuries sustained in automobile or military accidents, falls, or sports.6 Someone with a history of a previously torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or meniscus is 2.5 times more likely to develop knee OA and four times more likely to undergo an eventual total knee arthroplasty.7-9 Within the first decade after an ACL injury about 1 in 3 patients have radiographic OA, regardless of initial treatment strategy.10,11 Furthermore, surgical reconstruction and rehabilitation do not mitigate the risk of developing OA following ACL injury.12

Although injuries are not always avoidable, it pays to protect joints. All providers, especially those who regularly interact with athletes and sports enthusiasts, such as athletic trainers, physical therapists, sports medicine physicians, and fitness professionals, can advise patients or clients on the importance of wearing protective gear, like braces to prevent re-injury.13 In addition, participating in neuromuscular training exercises can reduce the risk for traumatic knee injury by up to 80%.14

Injury prevention activities such as stretching and strengthening exercises can be implemented in all levels of sports—from youth to professional levels—to protect athletes’ joints. Based on a comprehensive review of the literature, the OAAA Injury Prevention working group recommends that the following six core components (+ 2 optional components) be included in a structured warm-up during athletic practices to maximize effectiveness of lower limb injury prevention programs (LLIPP) for youth athletes.14 Handouts and videos for athletic trainers, coaches, athletes and parents can be found in the OAAA Injury Prevention Toolkit.

-

- Lower extremity and core muscle strength training

Click on this image to view the full Injury Prevention infographic. - Plyometrics – Jump Training

- Balance exercises

- Continual feedback to athletes regarding proper technique, including reminders to bend at knees and hips, to land softly, to keep knees over toes, and to avoid dynamic knee valgus

- Sufficient dosing: For optimal results from a LLIPP, a minimum of 6 weeks (about 2-3 fifteen minute sessions per week) is suggested as pre-season conditioning after which time the program should be used as a warm-up before practices and games for in-season maintenance.

- Minimal-to-no additional equipment is required. A mat for some of the exercises is desirable but not necessary.

- Lower extremity and core muscle strength training

- Optional Components

- Stretching: There is not enough evidence to support static stretching in ACL injury prevention. Dynamic stretching may be beneficial for other reasons, including perceptions about flexibility exercises being a critical aspect of warm-up activities, but additional research is needed to understand how stretching influences risk for ACL injury.

- Agility exercises: There is not enough evidence to support agility exercises in ACL injury prevention; although, the addition of this component creates an opportunity to add sport-specific training.14

While time constraints are a commonly reported barrier to implementing injury prevention programs,15,16 many organizations deploy warm-up activities that embrace some of the core components and only need minor adjustments to adopt a successful injury prevention program for their setting. Check out the Remain in the Game toolkit for coaches, which includes videos and workouts for team strength and flexibility movements. Keep players in the game with just 10 minutes of training at every practice!

While time constraints are a commonly reported barrier to implementing injury prevention programs,15,16 many organizations deploy warm-up activities that embrace some of the core components and only need minor adjustments to adopt a successful injury prevention program for their setting. Check out the Remain in the Game toolkit for coaches, which includes videos and workouts for team strength and flexibility movements. Keep players in the game with just 10 minutes of training at every practice!

Secondary Prevention

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

Clinicians should encourage individuals who are overweight or obese without symptomatic OA to lose weight. A 10-pound weight loss in someone who is overweight can reduce the risk of knee OA by 50%.17

Weight loss counseling is a key component to successful weight loss in patients. The CDC reports that adults with arthritis who are overweight or obese and who receive provider counseling about weight loss are four times more likely to attempt to lose weight; yet, fewer than half of those adults are receiving such counseling.18 Healthcare providers can engage patients in weight loss counseling with successful strategies such as motivational interviewing and the 5As of Obesity Management19 to better advise and assist the patient, guide the patient to programmatic resources, and simply educate patients that even a small amount of weight loss can significantly reduce joint load and pain but is also achievable.20 See Engaging Patients in OA Management Strategies module for counseling strategies.

INJURY PREVENTION

There is a critical need to develop, disseminate, and implement secondary prevention strategies to help patients after an initial injury.22,23 Secondary prevention strategies after a joint injury may include education, self-management, low-impact aerobic exercise, weight management, and prevention of a new joint injury (see section above). Injury prevention is particularly relevant for patients with a history of injury because a prior injury is a risk factor for a new injury.24,25 Furthermore, encouraging physically active individuals who are obese or overweight to participate in injury prevention training programs may be beneficial as they are at greater risk for injury than peers with a lower body mass index.26,27

Fall Prevention Resources

Patients who have had a fall or are at risk of falling can build strength and improve balance to reduce their risk of fall-related joint injuries and should be counseled to engage in or increase their physical activity.

The CDC’s STEADI initiative (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, & Injuries) includes educational materials for providers and handouts for patients on preventing falls.

The National Council on Aging’s Falls Prevention Resource Center offers resources and handouts for providers and patients.

Additional Resources for Providers

- NEW! Continuing Medical Education course for healthcare providers: Exercise Prescription for Osteoarthritis and Weight Management. Learn about strategies and resources to help your patients with osteoarthritis pursue physical activity safely and effectively. This activity has been approved for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™.

- National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Prevention of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury (Padua DA, DiStefano LJ, Hewett TE, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Prevention of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Journal of Athletic Training. 2018;53(1):5-19.)

- Athletic Trainers’ Osteoarthritis Consortium: The Role of Athletic Trainers in Preventing and Managing Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis in Physically Active Populations: a Consensus Statement of the Athletic Trainers’ Osteoarthritis Consortium (Palmieri-Smith RM, Cameron KL, DiStefano LJ, et al. The Role of Athletic Trainers in Preventing and Managing Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis in Physically Active Populations: a Consensus Statement of the Athletic Trainers’ Osteoarthritis Consortium. Journal of Athletic Training. 2017;52(6):610-623.)

- Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy and American Academy of Sports Physical Therapy: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Exercise-Based Knee and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention (Arundale AJH, Bizzini M, Giordano A, et al. Exercise-Based Knee and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2018;48(9):A1-A42.)

- Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guideline (Vuurberg G, Hoorntje A, Wink LM, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guideline. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52(15):956-956.)

- 2018 International Olympic Committee Consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis and management of paediatric anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries (Ardern CL, Ekås G, Grindem H, et al. 2018 International Olympic Committee consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis and management of paediatric anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2018;26(4):989-1010.)

- OAAA Consensus Opinion on Lower Limb Injury Prevention Programs: Recommendations for Essential Injury Prevention Program Components and Executive Summary

- Selected Issues in Injury and Illness Prevention and the Team Physician: A Consensus Statement (Selected Issues in Injury and Illness Prevention and the Team Physician: A Consensus Statement. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2016;48(1):159-171.)

- National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Conservative Management and Prevention of Ankle Sprains in Athletes (Kaminski TW, Hertel J, Amendola N, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: conservative management and prevention of ankle sprains in athletes. J Athl Train. 2013;48(4):528–545. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.02)

Patient Resources

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed resources to promote individual-level and community-level efforts to prevent and manage obesity. Printable handouts for patients include tips on fruits and vegetables, portion size, healthy beverages, and more.

- The Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) is a patient advocacy organization that offers a wide variety of brochures, guides and fact sheets on obesity and related topics including osteoarthritis.

CLINICAL TAKE-HOME POINTS

CLINICAL TAKE-HOME POINTS

-

-

- Clinicians should use the 5As and other motivational interviewing techniques to discuss the importance of weight management strategies among patients at risk for obesity or with obesity.

- Small changes in weight may profoundly alter the risk of OA.

- Clinicians should advocate for the use of injury prevention programs at local companies and organizations (e.g., youth athletic leagues, schools with athletic team).

-

REFERENCES

-

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Picture of America: Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/pictureofamerica/pdfs/picture_of_america_prevention.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Lubar D, White PH, Callahan LF, et al. A National Public Health Agenda for Osteoarthritis 2010. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39(5):323-326.

- Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High-Impact Obesity Prevention Standards. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/strategies/early-care-education/obesity-prevention-standards.html. Published 2021. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategies to prevent & manage obesity: Community efforts. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/strategies/community.html. Accessed Aprilhttps://www.cdc.gov/obesity/strategies/early-care-education/obesity-prevention-standards.html 22, 2019.

- Punzi L, Galozzi P, Luisetto R, et al. Post-traumatic arthritis: overview on pathogenic mechanisms and role of inflammation. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000279.

- Buys LM, Wiedenfeld SA. Osteoarthritis. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, M P, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 10e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Vina ER, Kwoh CK. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: literature update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):160-167.

- Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Niu JB, et al. The association of meniscal pathologic changes with cartilage loss in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):795-801.

- Luc B, Gribble PA, Pietrosimone BG. Osteoarthritis prevalence following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and numbers-needed-to-treat analysis. J Athl Train. 2014;49(6):806-819.

- Harris KP, Driban JB, Sitler MR, Cattano NM, Balasubramanian E, Hootman JM. Tibiofemoral Osteoarthritis After Surgical or Nonsurgical Treatment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture: A Systematic Review. J Athl Train. 2017;52(6):507-517.

- Padua DA, DiStefano LJ, Hewett TE, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Prevention of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. J Athl Train. 2018;53(1):5-19.

- Doherty C, Bleakley C, Delahunt E, Holden S. Treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent ankle sprain: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(2):113-125.

- Osteoarthritis Actional Alliance. Consensus Opinion on the Best Practice Features of Lower Limb Injury Prevention Programs (LLIPP). Available at https://oaaction.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/623/2018/08/FINAL_Consensus-Opinion_LLI-Prevention-Programs-Trojian-kra1.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- Padua DA, Frank B, Donaldson A, et al. Seven steps for developing and implementing a preventive training program: lessons learned from JUMP-ACL and beyond. Clin Sports Med. 2014;33(4):615-632.

- Bogardus RL, Martin RJ, Richman AR, Kulas AS. Applying the Socio-Ecological Model to barriers to implementation of ACL injury prevention programs: A systematic review. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8(1):8-16.

- Garstang SV, Stitik TP. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(11 Suppl):S2-11

- Guglielmo D, Hootman JM, Murphy LB, et al. Health Care Provider Counseling for Weight Loss Among Adults with Arthritis and Overweight or Obesity – United States, 2002-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(17):485-490.

- Obesity Canada. 5As of Obesity Management. Available at https://obesitycanada.ca/resources/5as/. Accessed February 22, 2019.

- Rose SA, Poynter PS, Anderson JW, Noar SM, Conigliaro J. Physician weight loss advice and patient weight loss behavior change: a literature review and meta-analysis of survey data. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(1):118-128.

- The Obesity Action Coalition. Public Educational Resources. Available at https://www.obesityaction.org/get-educated/public-resources/. Accessed August 9, 2019.

- Chu CR, Millis MB, Olson SA. Osteoarthritis: From Palliation to Prevention: AOA Critical Issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(15):e130.

- Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative (COAMI). A New Vision for Chronic Osteoarthritis Management. In: U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative, ed.2012: https://www.usbji.org/sites/default/files/COAMI%20Call%20to%20action.pdf.

- Driban JB, Lo GH, Eaton CB, Price LL, Lu B, McAlindon TE. Knee Pain and a Prior Injury Are Associated with Increased Risk of a New Knee Injury: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(8):1463-1469.

- Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Wolf SH, Padua DA, Cameron KL, Beutler AI. Association of Injury History and Incident Injury in Cadet Basic Military Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(6):1053-1061.

- Hruby A, Bulathsinhala L, McKinnon CJ, et al. BMI and Lower Extremity Injury in U.S. Army Soldiers, 2001-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(6):e163-e171.

- Kouvonen A, Kivimaki M, Oksanen T, et al. Obesity and occupational injury: a prospective cohort study of 69,515 public sector employees. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77178.

- Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, Sharma AM, Freedhoff Y. Clinical review: modified 5 As: minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(1):27–31.